Displacing Singapore

I wrote this essay in 1998, for a volume of photographs by Lucas Jodogne, titled Singapore: Views on the Urban Landscape. Lucas’ photographs were marvelous, a sort of warm version of the New Topographics. And I was in good company as a writer, the other contributors were curator Trevor Smith, Profs Lily Kong and Brenda Yeoh, Lee Weng Choy, and Lai Chee Kien. The essay is a bit dated now, and looking back I feel it was written a little pompously; blame the pernicious influence of Italo Calvino, who has led many fledgling writers astray: he is brilliant, but not someone to try and emulate. And I was a little harsh on the archaeological value of the work we did that afternoon. Even without a full excavation archaeologists can derive some data: a report on that salvage excavation by Goh Geok Yian and John Miksic can be found at epress.nus.edu.sg/sitereports/. Twenty-five years later, the story of Singapore’s pre-Raffles past is being taught in schools. We were just discerning its faint outlines when the essay was written.

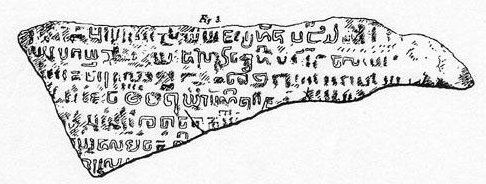

When this place meant something, many years ago, there was a boulder that stood on a sandy spit at the mouth of the Singapore River. Two meters tall, the boulder had been split in two, one face carved to receive an inscription. Of the inscription we know very little, for only fragments remain. It was an Indic script, marking the island’s relations with the powerful port kingdoms of the Malay World: Majapahit probably, the Empire of the Bael Tree, or perhaps the old Sumatran kingdom of Srivijaya.

Five hundred years ago, or a thousand, Singapore was one of the many ports that grew, flourished, and faded back into an ignominy of mud and mosquitoes, in time with the tidal ebb of trade, of power, of the varying charisma of princes and admirals. In the ninth century Singapore was Dragon’s Tooth Gate, a far port on the Chinese maps; in the 13th, she sent a tribute of elephants to the Great Khan.

In the 14th, judging from the old Annals, and from a few bits of celadon and a gold bracelet found on the Forbidden Hill that backs the river, Singapore was home to a prince, or princes. But we know little of these princes and their realm: was Singapore the temporary encampment for renegade prince on his way to found Malacca? Or was it a thriving city on its own, capital to three, or even five, generations of rulers, center of the Malay World, before Malacca? The Annals are ambiguous, yielding to many readings. Scholars are divided, or at least, resigned to uncertainty. Propagandists prefer not to dig too deeply. Archaeologists have nowhere left to dig: few patches of soil in Singapore remain undisturbed.

The Singapore Stone was the surviving witness to this history, to all the wealth and transience of old Temasek, of Sri Tri Buana, Parameswara and Iskandar Shah, the World Conqueror.

Munshi Abdullah, dedicated, compromised chronicler of early British Singapore, and the man who tutored Raffles in Malay, records how wise men from all of Singapore’s communities claimed the Stone for their own:

“The Indians declared that the writing was Hindu but they were unable to read it. The Chinese claimed that it was in Chinese characters. I went with a party of people, and also Mr Raffles and Mr Thomsen, and we all looked at the rock. I noticed that in shape the lettering was rather like Arabic, but could not read it.”

Some applied colored powders or lampblack to the stone, some took rubbings, some made castings, in an effort to better discern the outline of the blurred and worn characters. We will never know which wise man was closest to the truth, because in 1843 the Singapore Stone was broken up to make way for the house of the Harbormaster.

The few surviving pieces of the Stone — placed for safekeeping, or as a curiosity, on the veranda of the Governor’s Mansion — were hacked up by laborers for gravel a few years later, to pave the driveway. Three fragments remain to this day: two in Singapore’s National Museum, one catalogued but impossible to find, somewhere in the storage of the Calcutta Museum.

The Singapore Stone… de Casparis’ best attempt at a transcription

Singapore is a land that has misplaced its most ancient monument. Who is the wise man who will claim the emptiness that remains?

—

The city is constrained onto an island, and so all this ceaseless, nervous energy works upon itself, over and over again. Buildings are improved, upgraded, extended, torn-down and replaced, after brief years of service. Fortunes are made; roads are widened. New maps for new towns are overlaid completely on top of the old ones. The hills have been flattened, the swamps have long since been drained, and the coastline expands without cease, swelling into the sea, forcing a redrafting of all the maps, new surveys of all the boundaries.

The past continually makes way for a future that has no time to ripen into a present. And the citizens never imagine the city that awaits at the end of all that labor.

“If you ask ‘Why is Thekla’s construction taking such a long time?’, the inhabitants continue hoisting sacks, lowering leaded strings, moving long brushes up and down, as they answer,‘So that its destruction cannot begin.’ And if asked whether they fear that, once the scaffolding is removed, the city may begin to crumble and fall to pieces, they add hastily, in a whisper,‘Not only the city.” - Italo Calvino, Cities & the Sky 3, Imaginary Cities

Threatened by an approaching thunderstorm, we pick over the piles of earth. The construction site is idle. We have a few hours to retrieve what material we can from the excavated soil. This is Pulo Saigon. Once a waterlogged island, a bit of mud and mangrove, it has become part of the warehouse district that crowds both banks of the Singapore River along its short navigable length.

In the days ahead, the area is to be excavated, or rather, excised. Tunneling works will bring a new roadway from the north, under the Singapore River. At Pulo Saigon the tunneling will meet a long southwards running open cut, a huge trench forty meters wide, a hundred deep and 1500 meters long. After the excavations are complete, and tunnel joined to trench, the open cut will be covered over, forming a new surface over the underground roadway.

We are here on a salvage expedition. One of Singapore’s amateur archaeologists, perhaps its only, had come across some stones while examining the newly cleared site. The stones are interesting, but hard to read. They could be axes in the “smash-and grab” style of the later Neolithic. Or they could simply be oval-shaped rocks. Most examples of these axes are ambiguous at best. The prehistorian’s craft is a difficult one, worked at the margins of legibility. On the basis of these finds though, and given the site’s proximity to the river, Singapore’s only professional archaeologist thought it worthwhile to request permission to survey the site, and to rescue what material he could from the first layers of soil that had been cleared away.

The Public Works Department, and the contractor who controlled the site did indeed grant a window of time in which to work: three hours on a Sunday afternoon. And this is how we few volunteers find ourselves here, picking our way between the lorries, cranes and excavators marshaled for action for Monday, when the earth will be moved in earnest.

The piles of earth are full of material, rich in detritus. As the afternoon wears on, we don’t find any hand-axes, no prehistoric stones, nothing of the Neolithic. We do find plenty of colonial glass, and shards and shards of 100-year-old Qing blue-and-white, the rice bowls of Singapore’s coolies, who arrived from the same places their crockery did: Swatow, Amoy, Canton. We find fine-grained granite, from Southern China too, brought here as ships’ ballast, and used as paving stones, or discarded.

We find European stoneware, old gin bottles, and badly-fired old bricks, their centers still black with carbon. We find pieces of grey and black earthenware which could be a thousand years old, or a hundred, so common is this type of vessel to Southeast Asia.

And then, as large pregnant rain drops begin to fall around us, as the clouds loom lower, Chor Lin finds something else. Pieces of celadon, green glaze on a heavy stoneware body. Six hundred years old and made in China when the Mongols ruled, these pieces are contemporary with the fragments found downstream and across the river, on the Forbidden Hill. This is hard evidence that 14th century Singapore was a large, thriving city, with settlements on both banks, and this far up the river. One piece, two, three, then four, and then we scramble away, drenched and afraid of the lightening strikes that seem now to move between the cranes.

The next day, the bulldozers have their way, scrambling all traces. Four broken shards, from piles of disturbed soil. According to the standards of the archaeologist, this is meaningless, random information. We have found nothing.

Three months later, I walk across a traffic island on a freshly-made exit ramp for the new Ayer Rajah Expressway. The island has not yet been landscaped. The turf has not yet been laid. I notice shards of blue and white. I pick them up: Qing blue-and-white, the rice bowls of two generations earlier. The excavated earth we picked over weeks earlier has been trucked out and distributed around the island for landfill, bearing with it all its evidence, all its history, all its burden.

—

“It is pointless trying to decide whether Zenobia is to be classified among happy cities or among the unhappy. It makes no sense to divide cities into these two species, but rather into another two: those that through the years and the changes continue to give their form to desires, and those in which desires either erase the city, or are erased by it.” - Italo Calvino, Thin Cities 2, in Imaginary Cities

Singapore is a city that has misplaced its most ancient monument. Perhaps that is just as well, for no monument could be big enough to accommodate all of Singapore’s meanings and memories. No monument could be subtle enough in design to encompass all the comings and goings that this city has known.

But what about the landscape? The shape of the land, its forms and outlines, and buildings, corners, vistas, all of this read in the light of history, of experience. Isn’t this a kind of monument writ large, a visual reference point for everyone’s memories? Think of the long avenues of Manhattan, the seven hills of Rome, the Golden Horn, Parisian boulevards, Beijing’s precise orientation, its Drum Tower hill. In a sense, Singapore has misplaced this dimension of itself too, rubbed it smooth, made it featureless. The bodiless dragon, all head and no heart, Singapore, the imaginary city, has somehow succeeded in displacing its own landscape.

Since the founding of the modern settlement, nearly 200 years ago, alteration of the island’s coastlines and topography has been something close to an obsession. Sir Stamford Raffles personally directed the first landfill operations in late 1821, on the southern bank of the Singapore River, two-and-a-half years after founding his treaty port. Munshi Abdullah said it was like “men going to war”. Raffles wrote to England that

“I have had everything to new-mould from first to last; to introduce a system of energy, purity, and encouragement; to remove nearly all the inhabitants, and to re-settle them; to line out towns, streets, and roads; to level the high and fill up the low lands.”

Raffles’ successors followed in the same vein, driven by a vision of a hundred-year-effort to impose Western will on an Asian landscape, on Oriental peoples, on the myriad threats implied by, and excused by, a tropical climate. Independence thirty-five years ago brought different motivations, different rhetoric, but similar results, the continual remaking of the land.

If Singapore could be said to have a single landmark, it would be its skyline, seem from the sea. The vista has attracted attention for years, since draftsmen recorded its profile in all the illustrated journals of empire. But there have been three generations, in some cases four, of buildings in the prominent spots along the waterfront and Singapore River. One edifice has replaced another, and another, and so on. It is difficult, often impossible, to find the traces of one skyline in the contours of another seen 40 years later or earlier.

Today, some 18% of Singapore’s total area is reclaimed land. The Tian Hock Kian Temple, built on the beach by Hokkien sailors thankful for safe crossings, is now not one but three miles from the Straits, separated from the sea by the city’s current financial district, and further on, the reclaimed land that will be its financial district in thirty years. Most of the seaside villas of Singapore’s Jazz Age rich were torn down for condos years ago. The few that survive are now a mile from the seashore, separated by housing blocks, markets, shopping centers, the highway to the airport and a park. The islands off the southwestern coast of the island have been joined together to form an new island industrial site; the bays of the northwest have been sealed off and turned to reservoirs. At the eastern and western ends of the island, square miles of land have been added, industrial estates, housing, an airport, requiring the import of tons and tons of soil.

What is the genius loci of a place where the land beneath your feet is imported?

Still, this is no diatribe (though it may be as exaggerated). So what if Singapore has no landscape, in any full sense of the word? Perhaps it is better to be lost than found. Who needs all the bloody ballast of land and destiny? Singapore is about routes, not roots: an intersection point of the trajectories of a thousand journeys. Singapore is the sum of a hundred diaspora: at night, it seems everyone is dreaming about somewhere else.