the Merlion and other monsters

As an invented symbol, apparently born fully-grown from the head of an ichthyologist, the Merlion is most fully a monster, with its mixed charge of fear and attraction, for Singapore’s poets. It remains an object that some Singaporeans may love but most love to disdain. Of course a sense of belonging can be built around negative feelings as well as positive ones.

These are some notes, bits and pieces from an essay I wrote for Lim Tzay Chuen’s catalog in the 51st Venice Biennale, and they look at the history of the Merlion in some considerable detail. (You have been warned!) Click here for the Merlion entry in our general database of public art in Singapore.

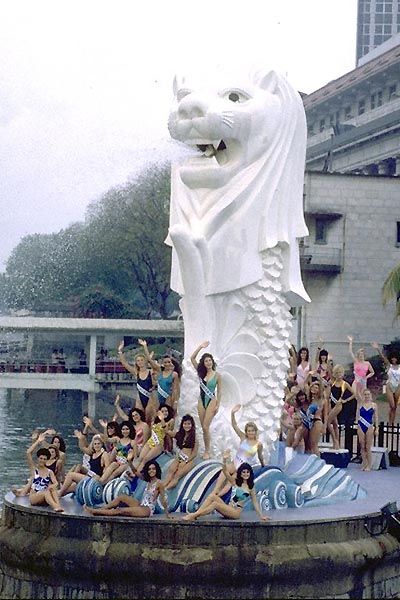

The Merlion was built of concrete over a steel frame, in Singapore in 1972, by Lim Nang Seng (1907-1987). It is 8.6 metres high and weighs some 80 tons. It is a half-lion, half-fish, standing on its tail fin, designed to have water jetting from its mouth. The work was commissioned by the then Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB) as part of a city-wide program to create tourist attractions and its design was based quite directly on the STPB’s own logo, itself developed only eight years earlier and credited to a Mr Frank Brunner. Mr Kwan Sai Kheong, a prominent educator, diplomat and amateur artist, is generally credited with the conception of the Merlion in its setting at the mouth of the Singapore River, while Lim was commissioned to execute the work, enlisting the help of his sons.

Monsters

The Merlion is a monster. Half-lion, half-fish, it is a monster in the original sense of the English word, at least according to the Oxford English Dictionary:

Monster: Originally: a mythical creature which is part animal and part human, or combines elements of two or more animal forms, and is frequently of great size and ferocious appearance. Later, more generally: any imaginary creature that is large, ugly, and frightening.

\n Singapore’s Merlion is large, and monstrous in its form, and in certain of the spaces it inhabits in the imagination, even if it lacks the ferocity, emotional charge and resonance of older, more feared monsters of the psyche. Even if it is a monster-lite.

Monsters light and heavy are a deeply rooted feature of the human imagination, in myth and art, from the antelope men of ancient cave drawings, through to centaurs, sphinx and griffin, makara, qilin, wyre-tiger, and kinnara: as many hybrid beasts as there are communities, storytellers and artists.

The genre of monsters created by adding fishtails to land beasts has a long geneology, stretching back at least to 8th century BCE Babylon (a relief from Khorsabad, 8th century BC, imagines a water-god as having a human torso and a fishtail).1 Lions with fishtails can be found on in the Sanchi stupas (below), at Mathura’s temples and the Ajanta caves2. In the classical world of the west, sea monsters were a well-established genre, and lions with fishtails are found on the coins of a Greek colony in the Crimea, and the Etruscan city of Populonia3.

These sea creatures seem to be the creation of a parallelism of imagination, a parallelism that extends the ideal types of the creatures of the world of land to each of the worlds of the air and of the sea, thus Tritons or mermen, mermaids, seahorses, dogfishes, eels for snakes and so on. This was a kind of predictable monstrosity.

The Merlion is a monster, but one which seems well-domesticated. Like all monsters, it is man-made, but in this case, fabricated quite deliberately and rationally for a particular instrumental purpose, to serve as a logo for a government agency. In 1964 the Merlion was selected as the logo for the new Singapore Tourism Promotion Board.

This complex, highly rule-bound graphic language got its start in the science of war, in the standards used to coordinate the movements of groups of men, warriors, over a landscape of battle. The system of signs that came to be known as heraldry began to develop in among the Crusaders of the 12th century, making use of the barely-remembered symbolic language of the armies of the Roman Empire, and as a key tool in the emerging pan-European chivalric culture, with its tournaments and its elaborated hierarchies and rules of precedence. The highly formalized and stylized verbal language of signs is readable to this day. And the “grant of arms” is still the business of the College of Arms of the Royal Household of Great Britain.

Monstrous creatures were well-established as part of the vocabulary of heraldry, as charges or elements that make up a coat-of-arms. Their composite bodies symbolized different combinations of qualities. Monsters could also be created through a process known in the profession as “dimidiation”, cutting each of two images in half, and joining two different halves at the middle, to make a new image.

The Norfolk port of Great Yarmouth provided ships and men to the British crown in the naval Battle of Soyl, 1350 CE. As a reward for the city’s service in the victory, King Richard II joined the heads of the three lions of the Plantagent arms to the tails of three Yarmouth herring (for Great Yarmouth was site of the famous Herring Fair), and three merlions, couchant instead of our Singapore Merlion’s rampant, have served as the town’s coat-of-arms to this day.

Here we have another example of a monster, half-lion, half-fish, created through a rational process of manipulation of visual symbols, to serve a particular political need. In this case the arms identified the town as an independent corporation, but recognizing a royal link and priviledges. (The lion-fish matched the symbolism of Yarmouth’s greater maritime rivals, the Cinq Portes, whose coat-of-arms comprises lions dimidiated with ships’ hulls.)

Heraldry was one of the means by which the emerging market towns and trading cities of Europe were able to visualize and present themselves into the hierarchies of nobility and lineage. Independent towns like Great Yarmouth were among the first such bodies corporate to be granted their own coats-of-arms.

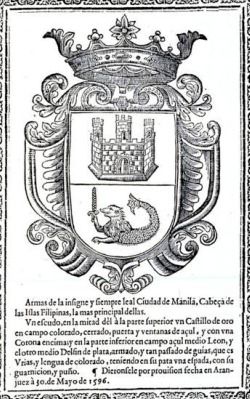

By the beginning of the 17th century, a similar marining of the royal lion, and that is the technical term, became a symbol of Europe’s enterprises in Asia. In 1596 the Spanish crown granted the city of Manila a coat-of-arms comprising a rather rat-like marined lion under a castle of gold.

Four years later, England’s royal household granted a coat of arms to that new monstrous creation of the city of London, a joint-stock corporation called the United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies, later known as the East India Company. The Company’s coat-of-arms (three ships of three masts below, a complex patchwork of fleur-de-lis, English lions and Tudor roses above) is supplemented by two figures that support the escutcheon itself, as the lion and the unicorn do the coat-of-arms of today’s House of Windsor. In the EIC arms, these two supporters are both marined lions, heraldic sea-lions, the “head and mane or, tails proper”. (The arms were changed with the establishment of the East India Company by Act of Parliament in 1698, and the sea-lions supplanted by more conventional terrestrial lions).

The Manila sea-lion lives on in the seals of the President and Vice-President of the Philippines, in the coat of arms of the Archbishop of Manila, and can be found as an element in the military ensignia of the Philippines and units of the American armed forces that served there.4

As so often in art history, it is difficult if not impossible to clearly establish the link between these merlions and the design or the designer of Singapore’s 1964 Merlion. At least one of the standard books of Singapore’s history, 100 Years of Singapore, published in 1921 and in print for many years after, does describe the seals of the East India Company.

Not inappropriate perhaps, but this is less than a positive reason for adding the fish tail to the lion. The seal of the Colony of Singapore, in use since 1867 and formalized by a Grant of Arms in 1911 was a straightforward lion and a tower, to symbolize the lion city. This formula was repeated throughout the years. Before launching the Merlion sculpture in 1972, the Board dealt explicitly with the reasoning behind opting for a “marined lion”, rather than a conventional one, as a symbol for the Lion City:

“When the concrete figure [of the Merlion] is officially unveiled later this year, emphasis will shift from the old Lion City concept to that of the Merlion City. The director of the Tourist Promotion Board, Mr Lam Peng Loon, explained: ‘Singapore needs a symbol that tourists can easily grasp, remember and associate with the Rupublic [sic]. Paris has the Eiffel Tower, New York its statue of Liberty and when you mention Australia people think of kangaroos. What have we got? Well, legend brings forward the idea of the Lion City, but this is hard to sell abroad because there is really nothing in Singapore today that supports it. A tourist may well ask, why Lion City? So we created a new symbol – a logical extension of the Lion City idea. Not a lion but a merlion, a creature with a lion’s head on a fish’s body.’”5

A tourist, or a reader, may well point out that there were more lions visible in the architecture of Singapore at the time the Merlion statue was commissioned than there were merlions, so the reasons that the merlion was deemed easier to sell than the lion alone is not really clear.

In the hectic, uncertain years after Singapore found itself independent, there was arguably only one attempt to create a truly national monument, as a national political project. The Foundation Stone of the Monument in Tribute to the Early Founders of Singapore was laid in 1971, dedicated by Singapore’s first President, Yusoff bin Ishak. It is a chaste monument, nearly mute (despite its long name). Indeed, as its name suggests, the effort to create a national monument hardly moves beyond the first signal of its intention. The memorial is a simple foundation stone, inscribed on four sides in the four official languages of Singapore, and mounted on a simple brick stand. Another empty pedestal.

The Foundation Stone of the Monument in Tribute to the Early Founders of Singapore

The Foundation Stone embodies a recognition of the gap between its ambitions and the poverty of the symbolic tools at its command to achieve them. Its designers recognize both the incompleteness of the Founders’ project, and how distant is a visual language that could possibly speak to their descendants. This recognition is itself a touching memorial, but there was no public protest when the Stone was removed to make way for a yet another road-widening project. Perhaps the most appropriate monument to the difficulty of Singapore’s nation-building project now lies unheralded in a cramped corner of the garden of Singapore’s National Archives. The problem with gestures, no matter how poetic, is that they can be easily missed.

In the years immediately after the Foundation Stone was put in place, a new team took on the task of Singapore’s monument-making. Reticence, sensitivity and restraint did not suit the needs of the Singapore Tourist Promotion Board (STPB), which decided that visual icons were necessary to market Singapore. This was not a question of nation-building, it was a simple functional requirement of the disciplines of marketing and tourism promotion.

In 1972 the head of the Tourism Board put the matter directly to the public:

“Singapore needs a symbol that tourists can easily grasp, remember and associate with the Rupublic [sic]. Paris has the Eiffel Tower, New York its statue of Liberty and when you mention Australia people think of kangaroos. What have we got?”6

\n Thirteen years later, a report from the Ministry of Trade and Industry rephrased the dilemma in marketing-speak:

“An identification landmark is a cost-effective way of projecting the image of a place as it can easily be put on print for use in advertising and promotion brochures. What Singapore suffers from is an identity problem as there is no landmark or monument which a tourist can easily associate Singapore with.”7

\n After several years of promoting the Tourism Board’s logo abroad in print advertisements, it was felt that the Merlion worked as a tourist icon. Plans were drawn up for an 8.6-metre scuptural version, eventually created by artist Lim Nang Seng, and installed in a prominent spot at the mouth of the Singapore River. This sculptural Merlion spewed jets of water from its mouth, into the Singapore harbour near the mouth of the river.

The Merlion was not the only “identification landmark” project on the agenda of the Tourism Board. Also in 1972, Thomas Woolner’s 1887 statue of Raffles suffered a strange indignity, not moved but worse, duplicated. It was cast and copied in white polymarble, and the same-size copy installed some 100 metres away, on a spot by the Singapore River said to be the place where Raffles actually first set foot in Singapore. The tourists pose for pictures next to what one map called “Raffles (white)”, while “Raffles (dark)”, the older twin, is somewhat neglected. The Merlion and Raffles: perhaps the STPB was hedging its bets as to which “identification landmark” would take root; in 1972 they also commissioned noted Johore potter Aw Eng Kwang to make 8-inch figurines of Raffles for sale as souvenirs.

No matter what one makes of its imagery, the Merlion’s original site was highly resonant and impressive, at the very mouth of the Singapore River, next to an ancient banyan with aerial roots stretching to the water. This spot was as central to the city as it was possible to get. It was possible, here, to smell the tidal mud and imagine the ancient seaport of Temasek/Singapore in the 14th century, to get a sense of time and history.

However the monument itself was positioned according to feng-shui principles, and could only really be viewed from across the river, along the pleasant walkway of Queen Elizabeth Walk. Lim Nang Seng’s oral history interview on file at the National Archives makes reference to his working with feng-shui master HC. Fine adjustments were made when the Merlion was placed in site, but with an overall result that pleased feng-shui master Huang Chien: “Very good, this is very good. This means that Singapore will have a very good position, for this is the dragon position, facing the world.”8

Indeed, the years from 1972 through 1997 mark pretty precisely the boundaries of Singapore’s long boom, a period of unprecedented economic growth. In 1997, a new bridge blocked off the Merlion’s view of the sea, and the Asian financial crisis brought a period of seemingly perpetual economic growth to an end.

Once in the Merlion Park itself, a tourist was confronted with an awkward back view of the part-lion, part-fish supposedly constructed for her benefit. The Merlion has little plastic quality, and that should not surprise. It is a two-dimensional logo translated from the page after all. The Chairman of the Tourism Board, Runme Me Shaw of the Shaw Brothers cinema empire, raised the problem while the larger Merlion was under construction. Lim Nang Seng offered to create a smaller, miniature Merlion not originally budgeted for, facing in the opposite direction from the larger sculpture, to pose for pictures. It was decorated with the same technique of ceramic cutwork used by craftsmen to decorate the roofridges of Chinese temples.9

Copying the Merlion

Twelve years on, the Tourism Task Force recognized that while the park attracted a million visitors a year, the ensemble was far from optimal for tourists:

“The statue of the Merlion, where it now stands, is very inconspicuously located. Tourists cannot take a well-angled photograph of the Merlion together with their relatives or friends.”10

\n “A photograph of the Merlion together with their relatives or friends…” As if the Merlion were a particularly amenable celebrity, but it this in fact the quality you want in an “identification landmark”. The Task Force Report called for a new Merlion “in a more prominent location. We recommend the Singapore River or the centre of the Marina Bay, where it can be surrounded by tall fountains and bright laser light to give the monument added ‘colour’”.11

This proposal was thankfully sidestepped a bit, and the new 38-metre Merlion later built far from the city on the resort island of Sentosa.12 So like Raffles, and for similar reasons, the Merlion was copied. This time it was reproduced at a different scale, as “Asia’s biggest freeform structure”, a superlative claim that has always been hard to pin down exactly.

Moving the Merlion

The 1997 eight-lane Nicoll Highway extension that cut the Merlion’s lines was a particularly awkward compromise in city planning. It now runs directly in front of Singapore’s original seafront Esplanade, spoiling a feature enjoyed by residents for some 150 years. The bridge runs close and higher than the original Merlion site, dominating it, cutting off its views, its access to the sea, and pretty much killing it as a monument or attraction. Here the Merlion mouldered and decayed, now placed in a backwater.

But happily, in 2002, the Merlion was rescued, moved and lifted and carried to the other side of the offending eight-lane highway. New pumps were put in to replace the old ones spoiled by silt. Nine small boxes with unknown contents were placed on the foundation of the monument. The new Merlion Park was indeed planned so as to yield “well-angled” photos, and has indeed become an attractive and popular tourist stop. Visiting the Park today one observes tourists contorting themselves, cupping their hands and opening their mouths wide. It seems like madness, until you realize that they are posing for photos, as if they are catching or drinking the water that jets, now with renewed force, from the Merlion’s mouth.

Mineralizing the Merlion

In the long view, cities can be seen as systems of organization and activity that can persist for centuries, outliving individuals of course, but also outliving empires and collective dreams of power. One of the characteristic attributes of the city is the creation of a series of physical forms, built structures, which are the output of the city-system but which then also act as inputs, constraining and modifying the possibilities of its continued operation. Manuel deLanda calls this a process of “mineralization”.13 Some of these artefacts, buildings or monuments, are more potent than others in structuring and ordering activity in these cities, not by their physical presence along, but mostly through their symbolic power.

From the point of view of individuals in a city, civic monument building is a risky, difficult business. Generally speaking, a monument needs a period of generations to reveal its influence at work, to see if it has taken root in its setting, become naturalized, shaped the further mineralization of the city.

Venice’s Lion of St Mark is a classic example. In 1293 CE, a lion “of oriental origin” was installed on top of one of the two great columns that frame the world’s finest urban public space, Venice’s Piazzetta San Marco. Before being hoist atop its column, the gilt-bronze lion, booty from Venice’s sack of Constantinople, was operated on, hybridized, given wings and turned into an air-lion. It was handed a book and transformed into a symbol of the city. The anonymous and well-travelled lion - already ancient in the 13th century - became the Wingéd Lion of St Mark the Evangelist. The airlion and the public space it overlooks have become a remarkably stable element in defining the mineralization of the city of Venice.

In the late 20th century, as Brenda Yeoh and T.C. Chang point out in their essay on “The Rise of the Merlion”, nation-building and tourism are the two distict projects which generate most attempts to create new civic monuments.14 The problem is that the symbolic projects are at cross-purposes, trying to say different things to different audiences in different languages. As we have seen, Singapore’s attempts to bolster its identity in a program of urban planning and urban monument-making have been highly problematic. Part of the problem has been an uncertainty about the shift between tourist and domestic registers. The planners themselves were clearly inexperienced and tentative (the Merlion pointed in the wrong direction for tourist photos). The myths themselves were fragile. There was no obvious choice of symbolic language to be used to express whatever stories, values and ideas are foregrounded.

Endings

Finally, no story of the Merlion and its appearances and disappearances would be complete without remembering another monument, one which stood at the exact spot of the Merlion’s original setting at the mouth of the Singapore River. The Stone was Singapore’s most ancient monument, dating at least as far back as the 14th century, a boulder two-and-a-half metres high and carved with fifty lines of inscription. It was never deciphered, and was exploded in the 1830s by British officials, to make way for the house of the harbormaster. Even its fragments were destroyed, or then later, dispersed and lost. The one piece now in Singapore’s National Museum had to be reclaimed from Calcutta, where it had been sent to the Royal Asiatic Society.

Even disappearance is a transformation with a formative power. The journey of all monuments eventually ends in obscurity.

Notes

-

T.H. White, The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation from a Latin Bestiary of the 12th Century, London: Jonathan Cape, 1954, p 252. ↩︎

-

K. Krishna Murthy, Mythical Animals in Indian Art, New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 1985, p 54. ↩︎

-

See this entry in the American Numismatics Association database of ancient coins, http://data.numismatics.org/cgi-bin/sgowobj?accnum=1949.100.8, accessed 2005. ↩︎

-

See the unit histories and arms posted on http://geocities.com/Pentagon8745/infanteria/ultramar/urespana.htm, accessed 2005 ↩︎

-

“Lion with a Fish Tail is Tourist Board’s New Emblem”, Straits Times, April 25, 1964. ↩︎

-

As quoted in “The Merlion is Singapore’s New Tourist Image”, Straits Times, August 9, 1972. ↩︎

-

And this was despite the Merlion having been place for 12 years already. Ministry of Trade and Industry, Report of the Tourism Task Force, bound manuscript, Singapore: MTI, 1984, p. 32 ↩︎

-

Lim Nang Seng, transcribed oral history interviews, Singapore: Oral History Department, National Archives, Accession number 413. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Report of the Tourism Task Force, p. 32 ↩︎

-

Ibid., p. 32. ↩︎

-

In 2019 it was announced that the Sentosa Merlion would be demolished, “Sentosa Merlion to make way for a new $90m themed linkway as part of Sentosa-Brani masteplan”, Straits Times, September 20, 2019 ↩︎

-

Michael de Landa, A Thousand Years of Non-Linear History, New York: Swerve Editions, 2000. ↩︎

-

Brenda Yeoh and T.C. Chang, “The Rise of the Merlion: Monument and Myth in the Making of the Singapore Story”, in Robbie B.H. Goh and Brenda Yeoh, editors,Theorizing the Southeast Asian City as Text, Singapore: World Scientific, 2003, pp. 29-50. ↩︎